The Season Has Begun

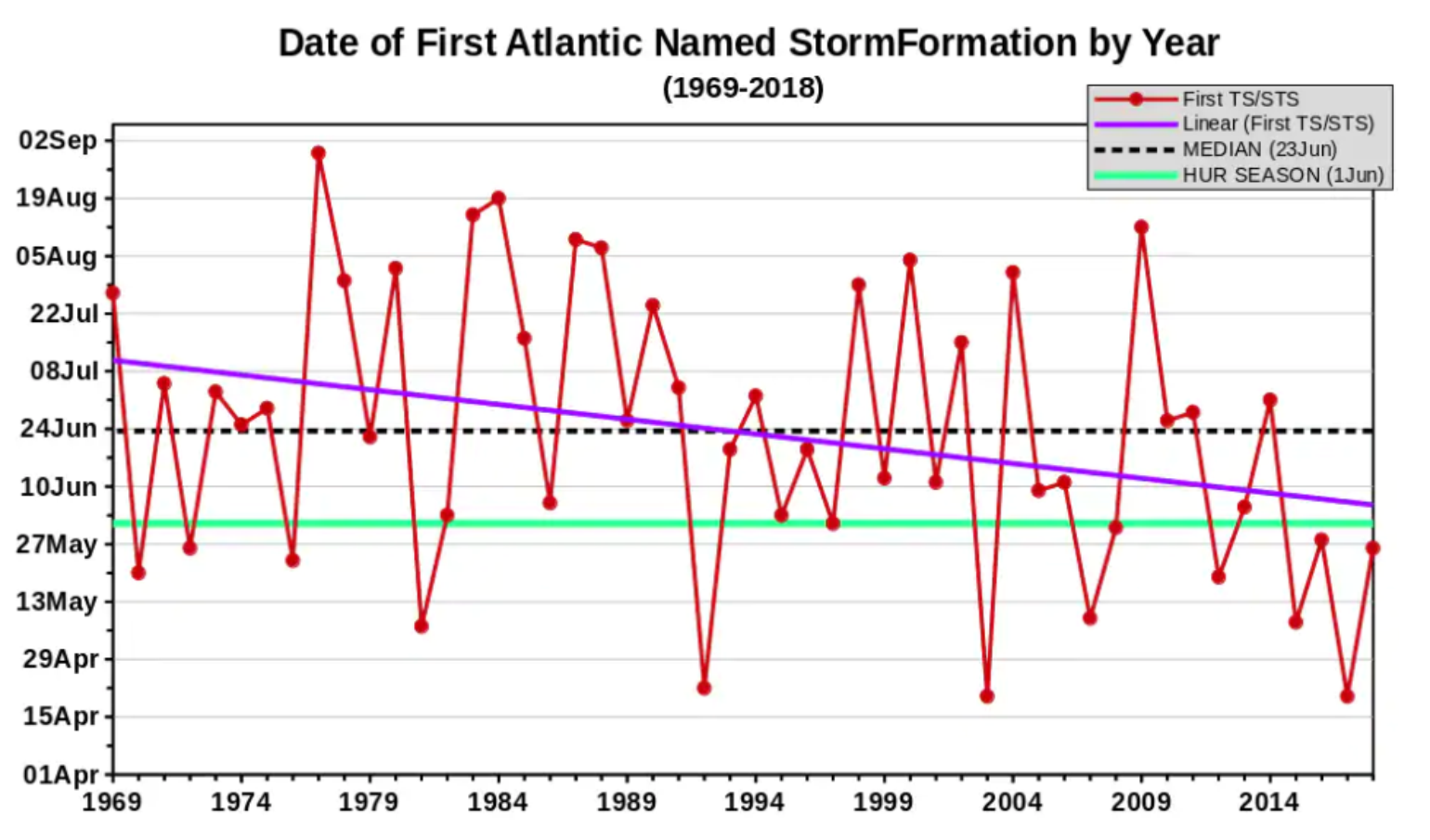

There has undoubtedly been a lot of attention given to severe weather across much of the U.S. since the end of April, but in the meantime, the Atlantic hurricane season has arrived. In fact, most people may not have noticed that the Atlantic Basin already had its first named storm (Andrea) of the season. Andrea was a short-lived (less than 24 hours) storm that formed on May 20, about 300 miles south of Bermuda. Andrea became the fifth tropical storm to form before the official start of the Atlantic hurricane season, which did not officially begin until June 1.

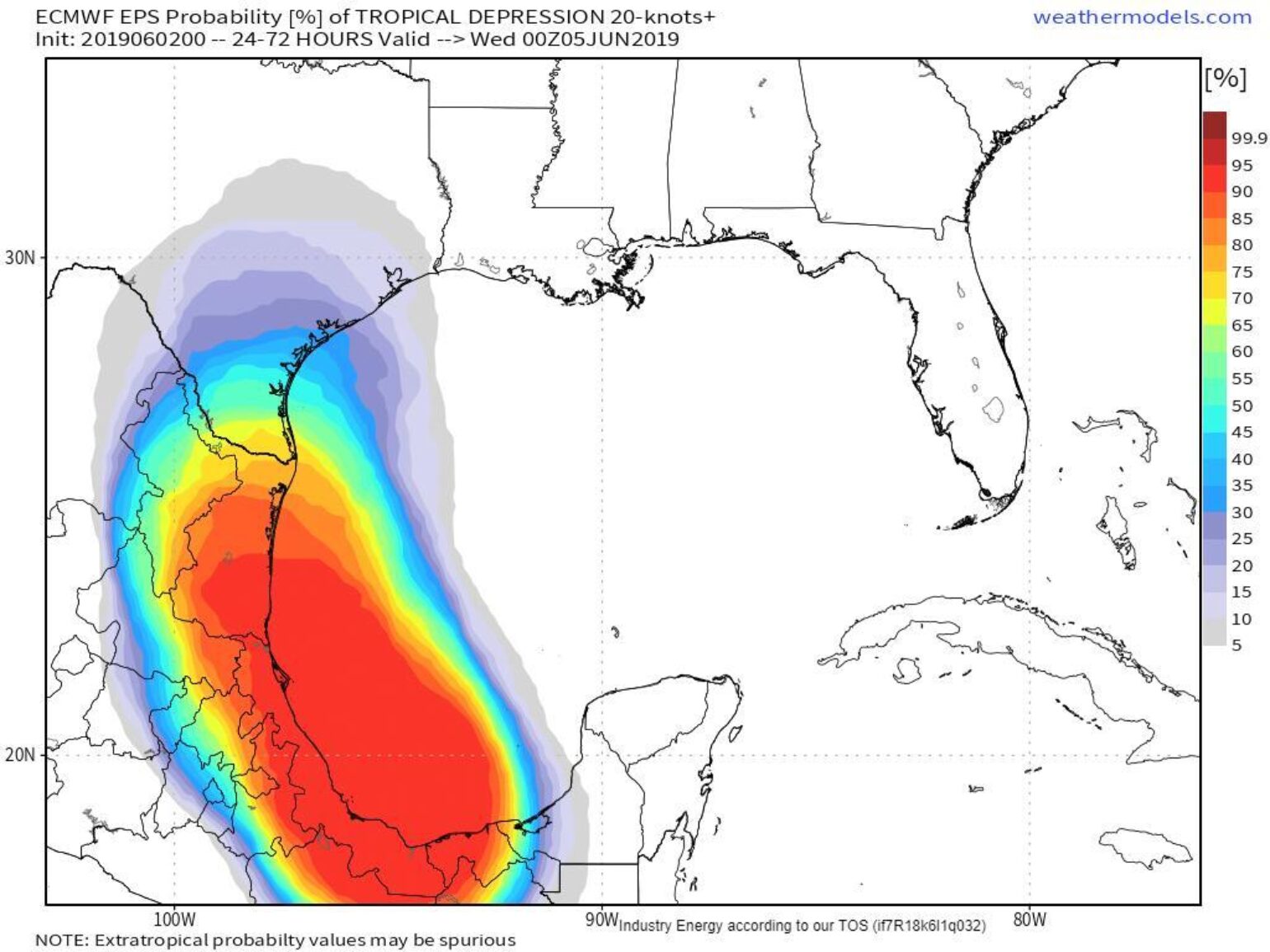

According to the National Hurricane Center, there is a 60% chance of named storm development in the near term in the southern Gulf of Mexico. It’s typical for us to see early season development in this area. At this time, most of the forecast models are bringing tropical weather up into Texas, which will also bring more moisture to the Central Plains where it is surely not needed at this time.

Seasonal Forecasts

I was recently asked: “Does the insurance industry place any weight on seasonal hurricane forecasts?” My quick answer was Yes and No, as it depends.

To elaborate on the Yes part: The insurance industry has always been supportive of seasonal hurricane forecasts by subscribing to private forecasting companies and by funding academic research in these areas. Most companies don’t like surprises and, naturally, being prepared is the logical thing to do for both the reinsurance and insurance industries. However, insurance companies may be more limited in what they can do than reinsurance companies.

The seasonal forecasts can influence the strategic planning of an insurance company by making sure they have adequate claims adjusters in place going into the hurricane season to better serve their customers. Of course, an active hurricane season might require an insurance company to consider service level agreements or loss adjustment expenses and the effects of demand surge that might need to be paid in an active hurricane season. However, since the insurance industry is heavily regulated, companies have little ability to adjust rates for an active or inactive season ahead of time. The reinsurance industry, on the other hand, can be a bit more opportunistic when dealing with seasonal forecasts in terms of planning ahead to provide reinsurance in the secondary market.

To the No side of the answer: Capital requirements for insurance companies are regulated by rating agencies and the insurance commissioners of each state, and do not allow for rate adjustments on a seasonal basis. As part of its strategic planning, an insurance company may want to stress test a portfolio to a certain loss level, as it has the ability to buy more reinsurance during the season if it is uncomfortable with the potential losses that may come from a particular seasonal forecast. The extent of just how much seasonal forecasting plays into each insurance company’s strategic planning is unknown, but generally, insurance companies spend considerable time with strategic planning to understand the potential of losses in any given season, regardless of the Atlantic Basin seasonal activity.

From a business perspective, it’s hard to rely heavily on forecasting when the accuracy of seasonal forecasting is low. Historically, in June seasonal forecasts, the forecasting of activity has not correlated well with actual insurance industry losses. How many times have you heard about 1992’s Hurricane Andrew and how that season was a below normal year? Yet, Andrew happened and was a very big loss for the industry. “It only takes one” will haunt the industry until forecasting gets better.

The readers of my past Atlantic hurricane seasonal forecasts may know that I am all for our industry moving away from simply looking at activity in terms of the number of named storms and hurricanes the Atlantic basin might produce, and rather focus more on what the pattern is suggesting in terms of landfall impacts. This is where we will find the most value, as I describe in more detail below.

Seasonal Forecast and Landfall Threats

The seasonal forecasts we see each year from various sources that provide a number range of expected named storms and hurricanes in the Atlantic Basin are a dime a dozen. There is usually a considerable spread in these forecasts. Currently, there are 19 different forecast groups that have submitted Atlantic seasonal hurricane forecasts to http://seasonalhurricanepredictions.bsc.es/ . The average of these forecasts calls for 6 hurricanes, which is closer to an above normal season.

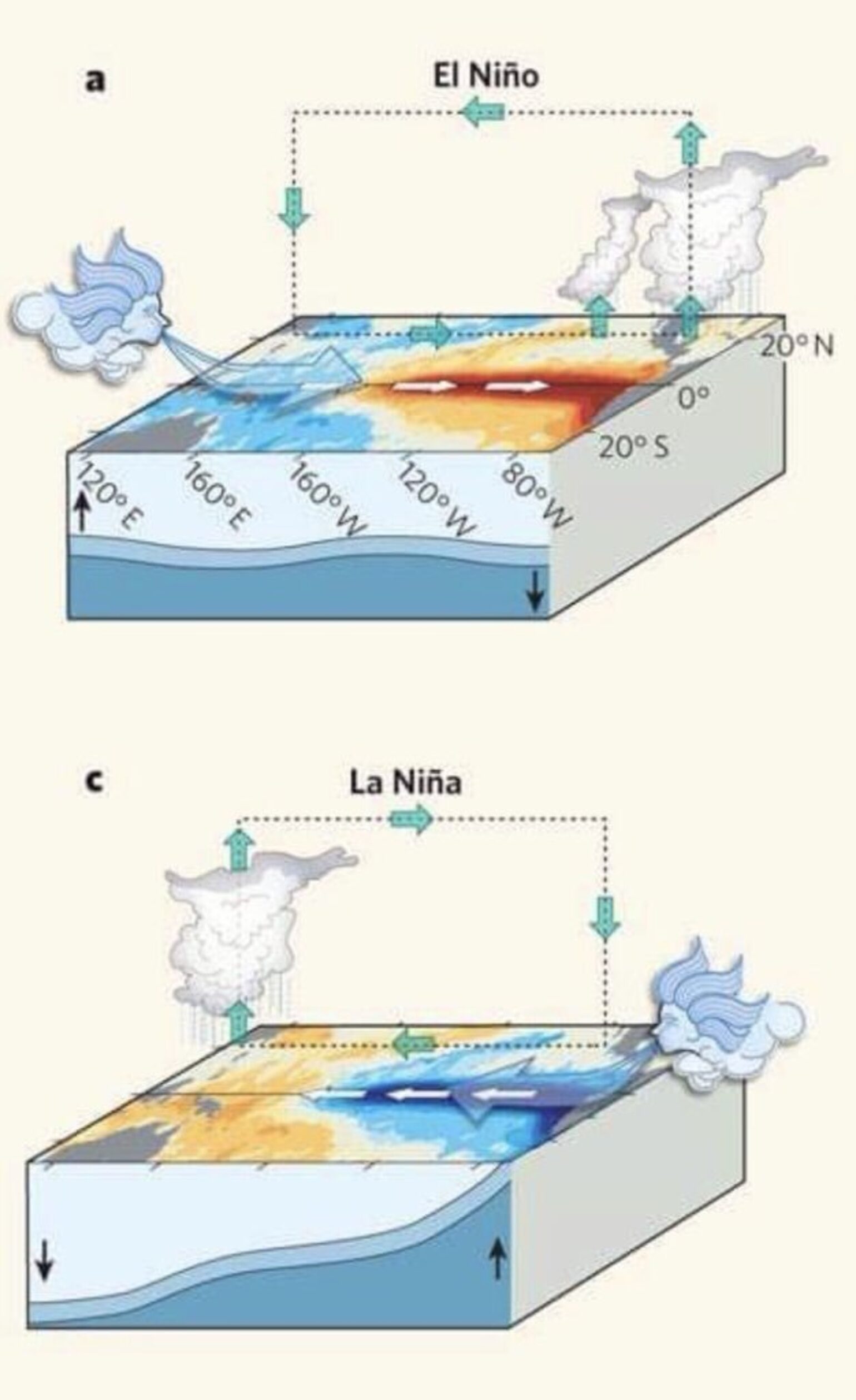

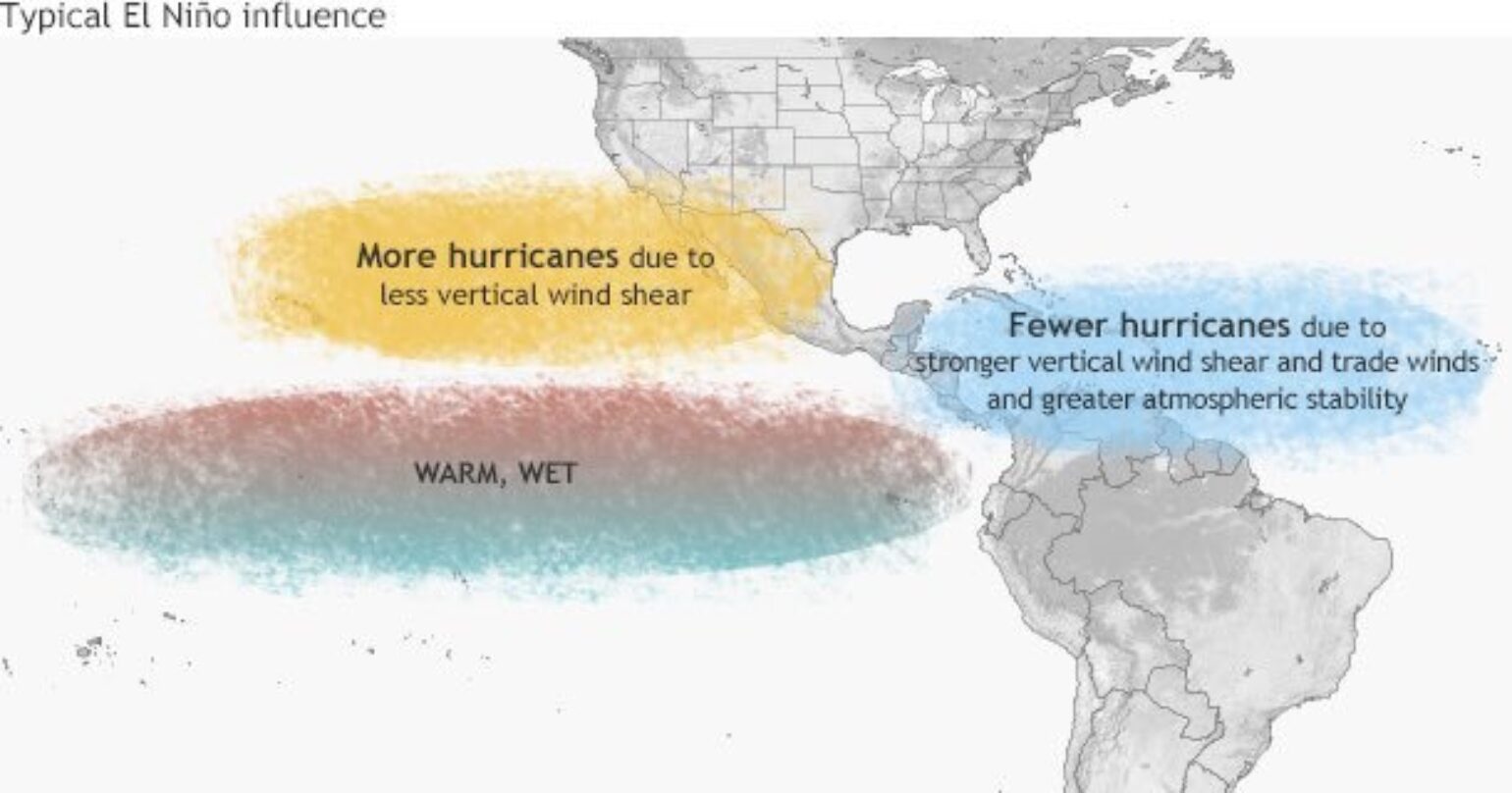

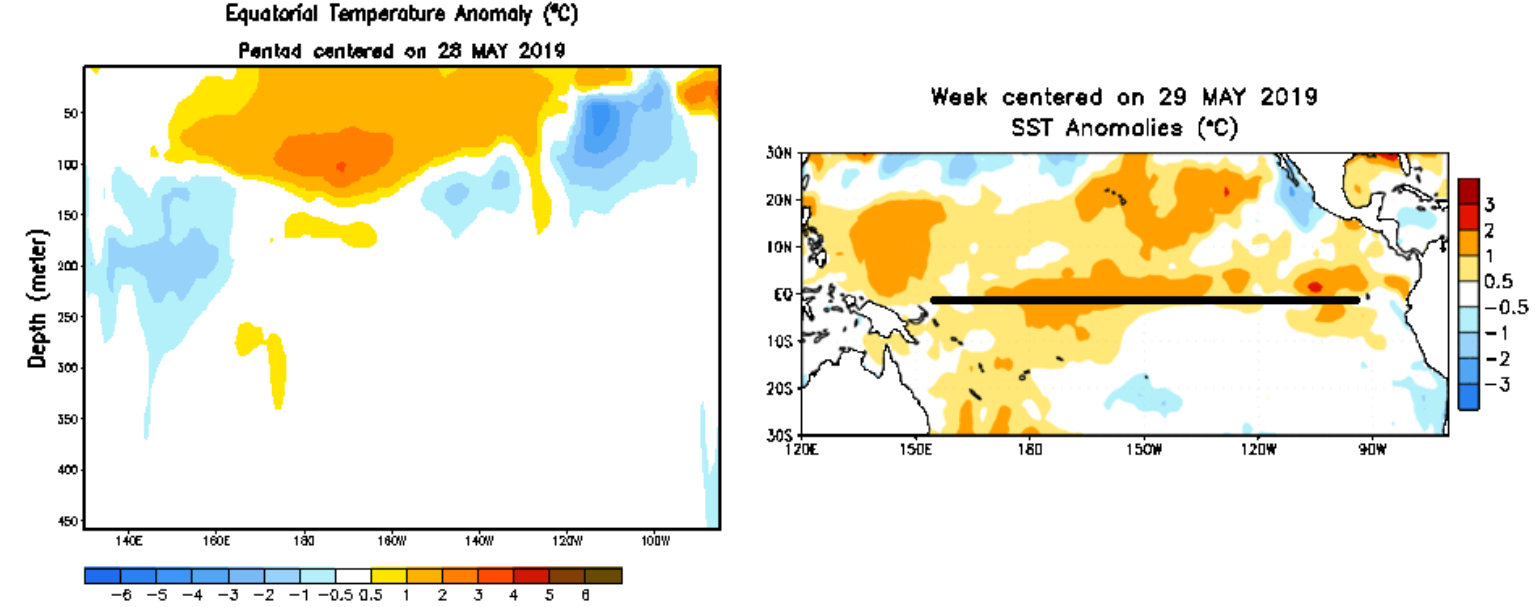

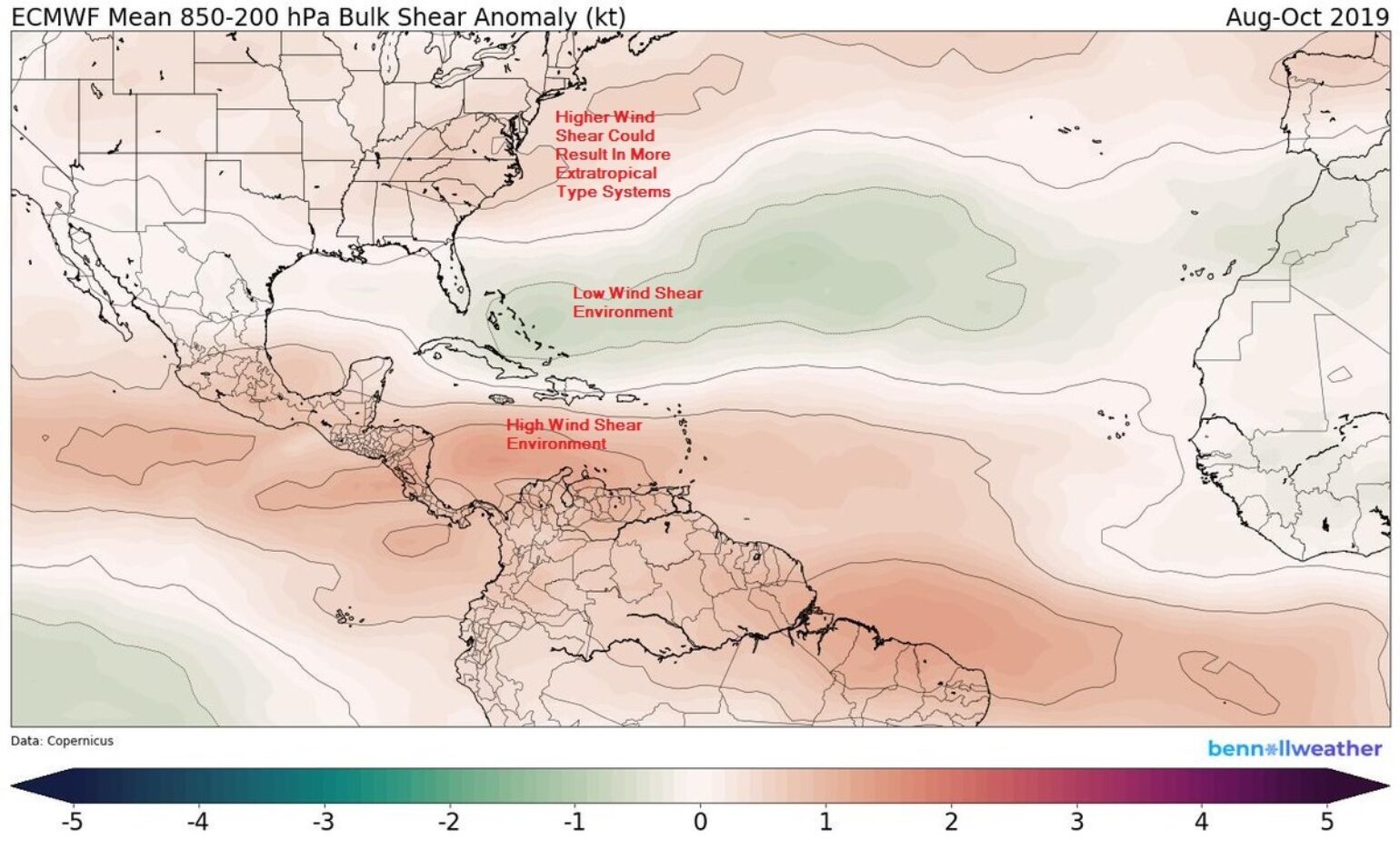

One of the major factors being considered in many of these forecasts is what the state of El Niño Southern Oscillation (ENSO) may be during the hurricane season. Currently, there is a weak El Niño occurring in the tropical Pacific, and this is forecasted to maintain into the heart of hurricane season. El Niño historically limits named storm development by increasing wind shear across the Caribbean and the Main Development Region. However, not all El Niños are the same, and this El Niño is a Modoki El Niño. This means that the warmest water is found in the central Pacific rather than off the coast of South America. We may see less of an overall impact on Atlantic hurricane season activity with a Modoki El Niño.

Another factor to consider, which I think some of the seasonal forecasts may be missing, is that the depth of warm water is shallow and there is actually cooler than normal water beginning to show up at depth, which actually suggests more of a La Niña signature. This could mean that we see very little El Niño impact this hurricane season and instead begin more of a transition to a La Niña weather pattern for 2020.

Sea Surface Temperatures across the Atlantic are currently warmer than usual, which would suggest a more active season. However, we may also want to consider one of the indexes that the insurance industry has looked at for over two decades now. According to Colorado State University, the Atlantic Multidecadal Oscillation (AMO) is currently in a cold phase, which historically would limit named storm activity in a given season, however, SST will be plenty warm enough for named storm development.

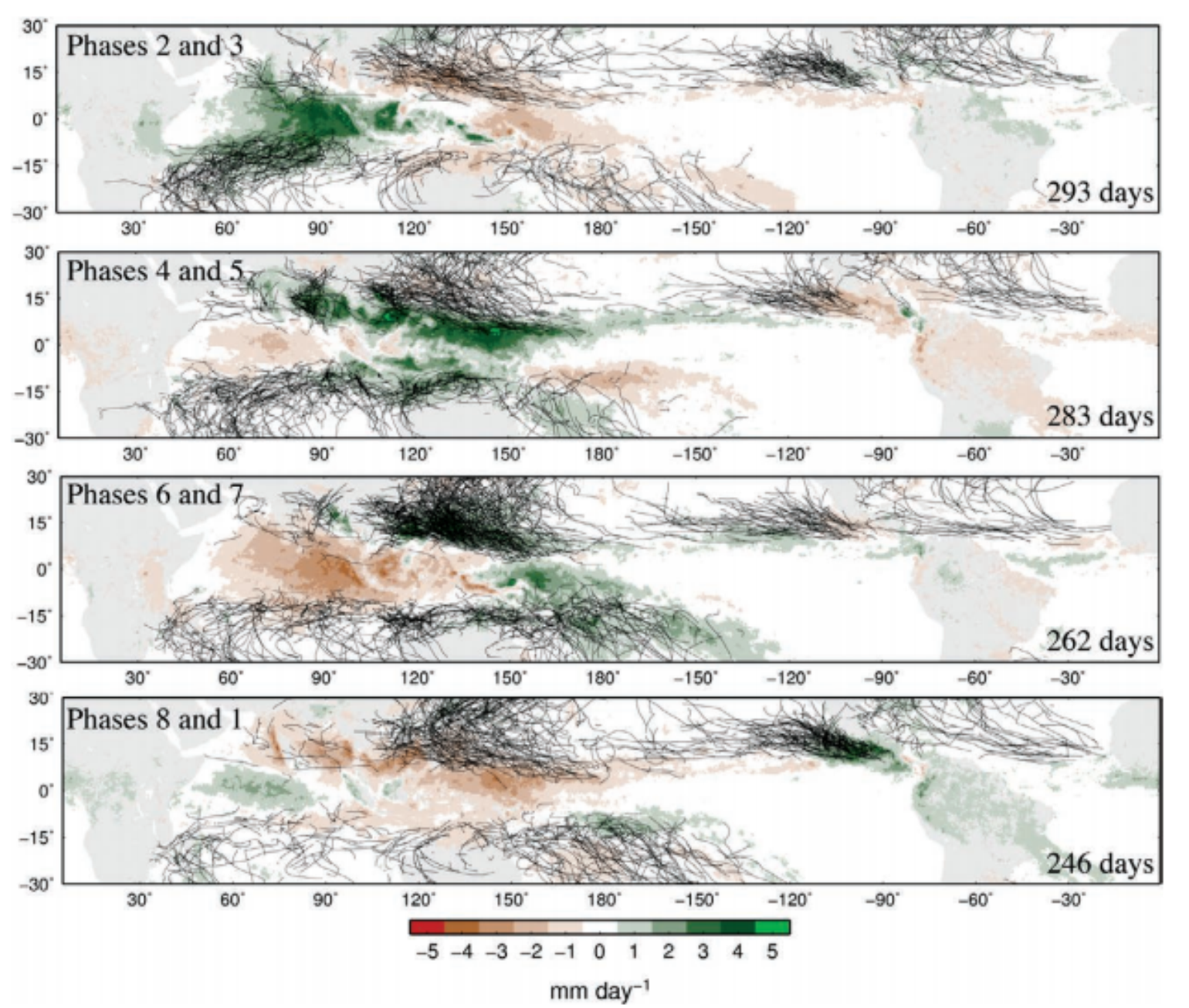

The other two factors to watch this Atlantic hurricane season will be Saharan dust and the Madden Julian Oscillation (MJO). Both of these are difficult to predict at seasonal time scales, but understanding the phases of the MJO can help determine when named storm development will occur. The MJO is the major fluctuation in tropical weather on weekly to monthly timescales that comes from pulses of tropical convection over the subcontinent of Asia. The MJO can be characterized as an eastward moving 'pulse' of cloud and rainfall near the equator that typically recurs every 30 to 60 day. In fact, the Atlantic basin is currently going into a phase (The MJO is currently in phase 3 and about to enter phase 4) that is not conducive to tropical development. It would appear unlikely that anything of substance develops in the Atlantic Ocean through early July as El Niño and the phase of the MJO limit convection development, which would also limit named storm development.

Overall, it looks like we have the potential for another late blooming season for 2019 with some subtropical development between now and the middle of July, along with a chance for a weak named storm in the Gulf of Mexico this week.

Saharan dust can be an inhibitor of Atlantic Hurricane activity, but it often moves off Africa in waves. In between these breaks of dust, and when combined with the right phase of the MJO, you can find that named storm development has a higher probability of occurring.

Summary

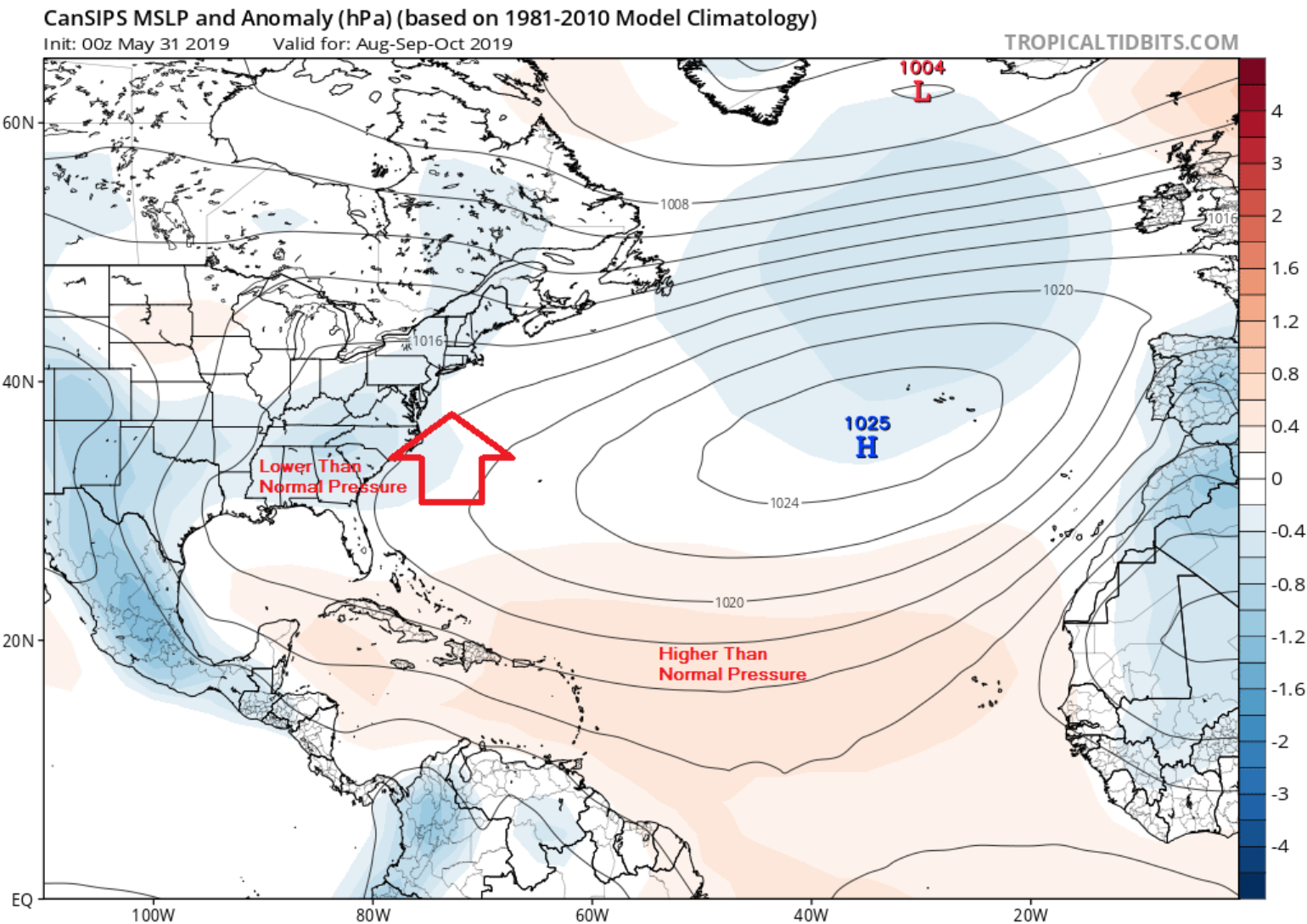

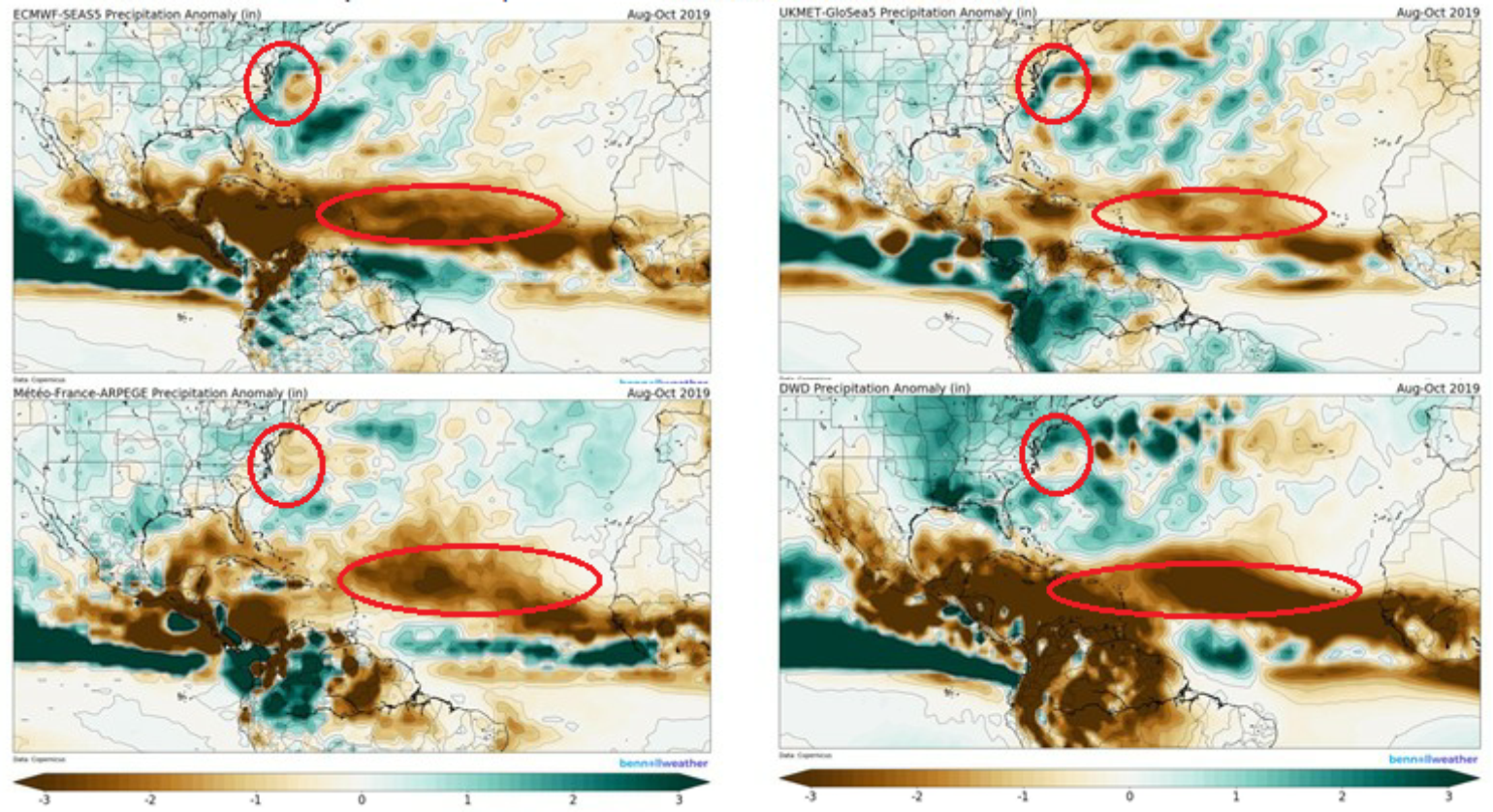

I am expecting a more active than normal (Named Storm and Hurricane Storm Counts) Atlantic hurricane season as I think the Modoki El Niño will have less of an overall impact. When one combines this with the warmer than normal SST and weaker than normal wind shear near the East Coast, the conditions should allow for more than normal named storm development. The climate models are suggesting above normal precipitation on the periphery of the west side of the Bermuda high, which could come in the form of named storms during the summer months. The key to the overall season will be how the MJO and Saharan dust enhance convection, with the next best possible window after this week coming in early July. How all of this insight will impact the insurance industry is a big question at this point in time, but risks along the East Coast need to be watched.