No Rest for the Weary

The Atlantic hurricane season is far from over. In fact, we are just a few days removed from the peak of the season. As mentioned in the September 6th BMS Insight, I anticipated the insurance industry would have a solid seven days of rest, but this was in regard to new tropical development. The insurance industry is grappling with the outcome of Dorian and the under-reported major Category 4 Typhoon Faxai that had a direct hit on Tokyo this past weekend. The NHC has now classified potential tropical cyclone number nine (PTC9) in the central Bahamas, and the long-range forecast still suggests the end of September and beginning of October could have several named storms develop in the Atlantic Basin - there is no rest for the weary.

Basin Memory

If you have been keeping track of the tropical troubles so far this season, there is clearly a target on areas around eastern Florida and the Bahamas. Dorian is not the only storm to impact these locations; Hurricane Chantal’s origins started in this area, along with Tropical Storm Erin. Tropical Depression 3 also made a brief appearance there as well.

This is a great example of weather memory or, more commonly known to the catastrophe modeling industry, clustering. It is a fairly typical occurrence when the atmosphere repeats a particular type of weather pattern. We see this with floods, severe convective storms, winter storms and with tropical weather events. There are many reasons why the atmosphere has clustering. Different modes of atmospheric variability such as the Atlantic Meridional Mode (AMM), El Niño-Southern Oscillation (ENSO), North Atlantic Oscillation (NAO) and Madden-Julian Oscillation (MJO) have been shown to affect Atlantic hurricane activity through changes in atmospheric steering currents and vertical wind shear.

In fact, a good understanding of clustering in the Atlantic Basin is found in the paper by Kossin et al. (2010) which shows four distinct clusters of storm activity that are common across the Atlantic Basin. The best recent example of this might be the 2004 Atlantic hurricane season with Frances and Jeanne taking similar tracks and making landfall along the east coast of Florida, basically in the same general area and 21 days apart. There are many historical examples of clustering, such as Hurricanes Connie and Diane in 1955, which hit the Carolinas just six days apart. Because of this, some of the catastrophe modeling companies simulate clustering into their event catalogs allowing for a probability of multiple events within a season to impact similar areas of the U.S coastline.

Future Humberto?

For the last several days, there has been a tropical disturbance labeled PTC9 over the central Bahamas which is slowly becoming better organized. The National Hurricane Center gives it an 80% chance of becoming a tropical depression or storm in the next 48 hours and a 90% chance in the next five days. Humberto is the next name assigned for the 2019 Atlantic hurricane season.

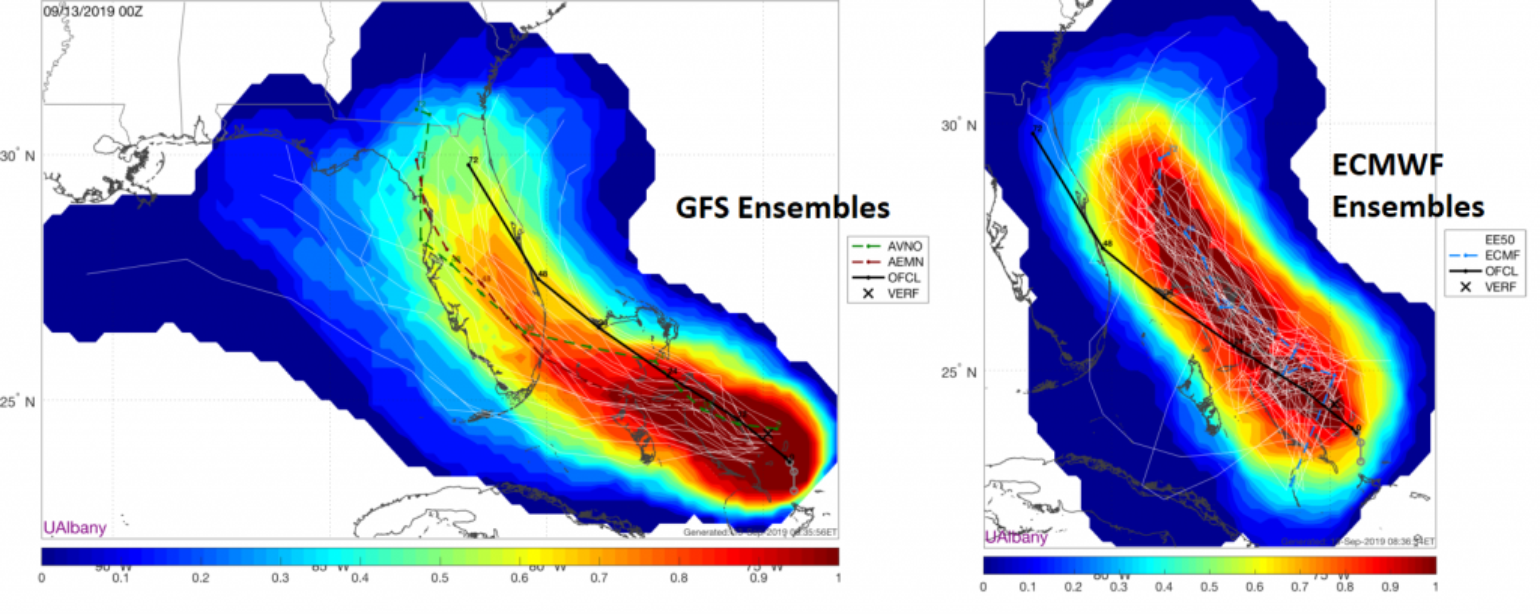

As mentioned with Dorian, the weather forecast models have a hard time modeling ragged, sloppy, and weak tropical storms. The current modeling suggests almost every scenario imaginable. For example, the American Global Forecast System (GFS) keeps the system weak as a tropical depression or tropical storm, which could result in more insurance claims than what occurred with Dorian due to heavy rainfall and locally strong gusty winds reaching the U.S. As a counterpoint, the European Centre for Medium-Range Weather (ECMWF) indicates PTC9 will develop faster and stronger and holds it off the southeast coast of the U.S. Given the track record, I would have to buy into the ECMWF model, which makes sense if the system can stay over the warm Gulf Stream between Florida and the Bahamas. It will likely strengthen and mirror the track Dorian followed a few weeks ago. Similar to Dorian, if PTC9 develops into a hurricane, the strongest winds will remain offshore, but this will depend on its track up the Florida coastline. The majority of ECMWF ensemble guidance is keen on keeping PTC9 far enough offshore to limit any impact of wind, with the long-range forecast suggesting the system will take a right hook and move out to sea early next week. However, Florida, Georgia, the Carolinas, and even Bermuda still need to pay close attention to potential damage as, currently, the system is weak and leading to higher model uncertainty.

Future Tropical Troubles

PTC9 might not be the only activity into early October as there is a signal that the MJO will aid in a broad-scale rising motion in the upper atmosphere, which will promote named storm development across the Atlantic Basin. Currently, there is large-scale sinking motion across the main development region which has likely contributed to the lack of activity in this area of the Atlantic. Multiple waves have come off of Africa, but have failed to develop into a storm since Dorian. The MJO is a large overturning circulation that propagates east across the globe about every 30 days. Think of it as a wave, the leading edge of which is “suppressed” and causes sinking air. In the backside of the wave, the air is more prone to rising, which aids in named storm development.

The first concern for the insurance industry is PTC9, but later next week there could be other tropical troubles starting to take shape from the Gulf of Mexico to the African coastline.