Australia has been the recent focus of global media attention due to the severe bush fires and hail storms that occurred over the Australian spring months. However, questions remain if the impact to the Australian insurance industry will continue into the summer months, and if there should be heightened concern regarding the active Australian cyclone season that is already a month old.

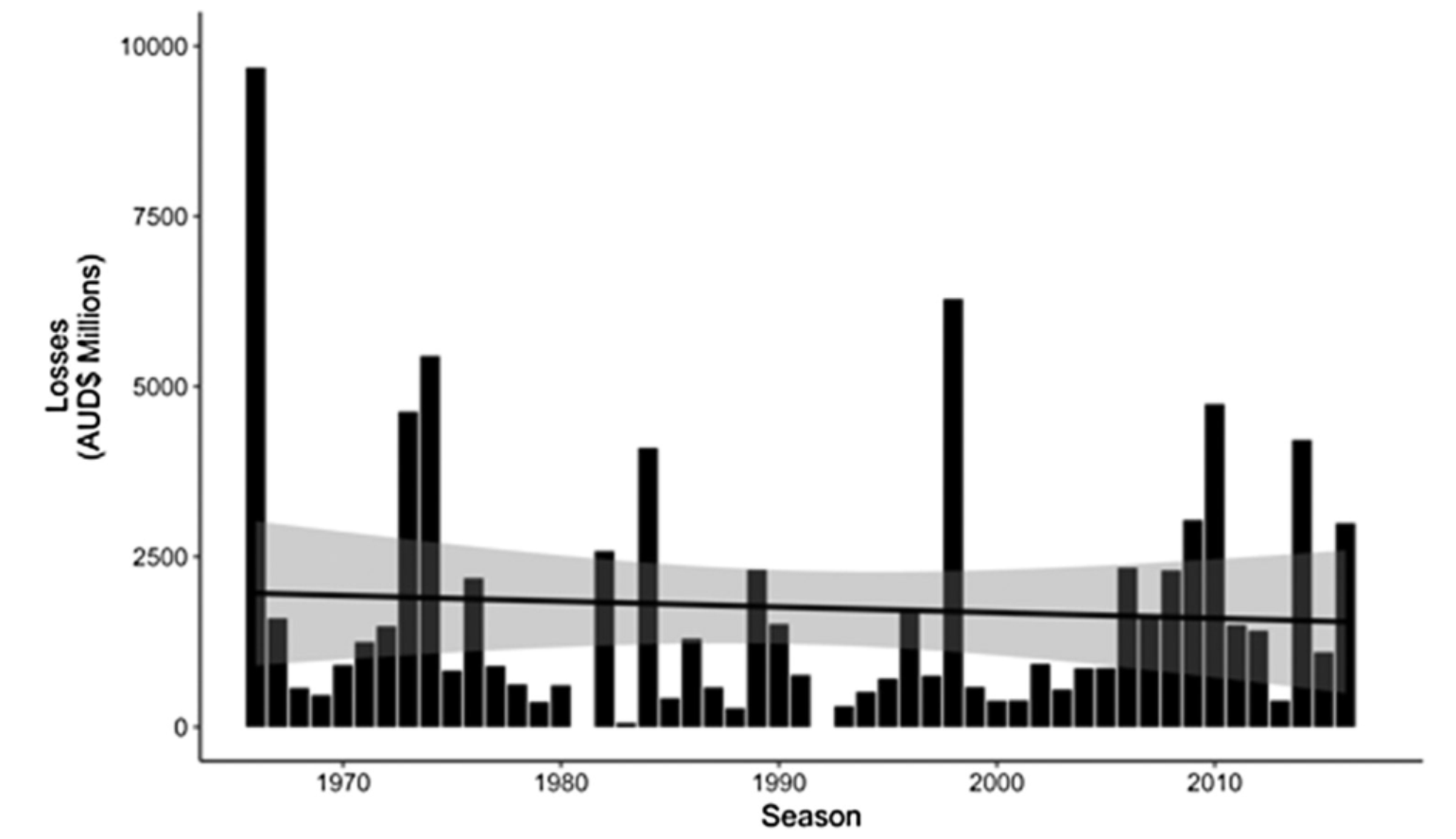

The 2018 and 2019 storm seasons have been costly for Australia’s insurance industry, and the recent bush fires and hail storms will only add to the total loss this year. Bush fires, which continue to burn across New South Wales, have garnered worldwide attention since an estimated 104 fires are yet to be contained. Interestingly, bush fires, historically, have accounted for only about 12% (or AUD $11.1B) of the typical losses in Australia, but that does not mean fire losses couldn’t easily climb higher as they have in the U.S. in recent years. As a counterpoint, floods are also a well-known problem in parts of Australia and actually account for more loss than fire at 15% (AUD $13.6B). Hail events account for about 27% (AUD $25B) with, notably, the 1999 Sydney hailstorm at AUD $5.6B being one of most expensive events to ever occur in Australia. The most costly peril historically, however, is cyclone, which accounts for 29% (AUD $26.1B) and is why the cyclone season is so closely watched. However, even with the annual occurrence of large catastrophic events, a new paper by McAneney et. al (2019) suggests there is no trend in normalized losses from weather-related perils, which account for 94% of losses in Australia, when such losses are aggregated.

Although the bush fires and recent hail storms have been devastating, it is important to remember that, with every passing year, a greater percentage of the population is moving to large urban centers, such as Sydney. These urban centers are expanding into the bush fire risk zones, so perils are impacting a larger portion of the population than what was previously the case. The population is also expanding along the coastlines, which will make the threat from cyclones even more costly over time. Although the rising cost of natural disasters is grabbing the media attention, the cost of these natural disasters is being driven by where and how a society chooses to live. When more people live in vulnerable locations with more to lose, it follows that costs will rise. This is why it is important to look not only at loss trends, but also to consider the various trends in weather perils that cause the loss. After all, there’s no such thing as a natural disaster – only natural occurrences which become disasters because of human interaction.

Eyes on the Cyclone Season

With most of the ocean basins that produce named tropical cyclones now cooling in the winter months in the Northern Hemisphere, the Southern Hemisphere oceans are heating up. Since Australian cyclones contribute to the highest proportion of the historical loss, there is a watchful eye on these seasonal forecasts. Currently, the largest Australian climate forcers are driven by two significant ocean sea-surface temperatures (SST) signatures, namely the El Niño Southern Oscillation (ENSO) and the Indian Ocean Dipole (IOD). Most have heard and know about what impacts ENSO can have across the continent and on the Australian cyclone season. SST anomalies across the equatorial Pacific Ocean, which is where ENSO is measured, had been typical of a neutral ENSO phase since April 2019. The negative phase of ENSO (La Niña), which tends to bring flooding rains and higher cyclone landfall probability to Queensland, is not forecasted to develop. The international climate models continue to indicate that the neutral conditions will likely persist until at least February of 2020. Generally speaking, a neutral ENSO phase has little influence on Australian weather. However, Australia as a whole just had its driest spring ever recorded, and the mean maximum temperature was the second warmest on record – typical of a positive phase of ENSO or El Niño. With ENSO neutral conditions in play, however, something else is driving these extremely dry conditions and above-average temperatures across the continent, which have likely contributed to the large bush fire risk across New South Wales and Queensland. If ENSO is neutral, the lesser-known IOD, which is one of the strongest in the last 60 years, seems to be the main climate forcer impacting Australian weather patterns currently. This strong positive phase creates a drying influence over parts of the country.

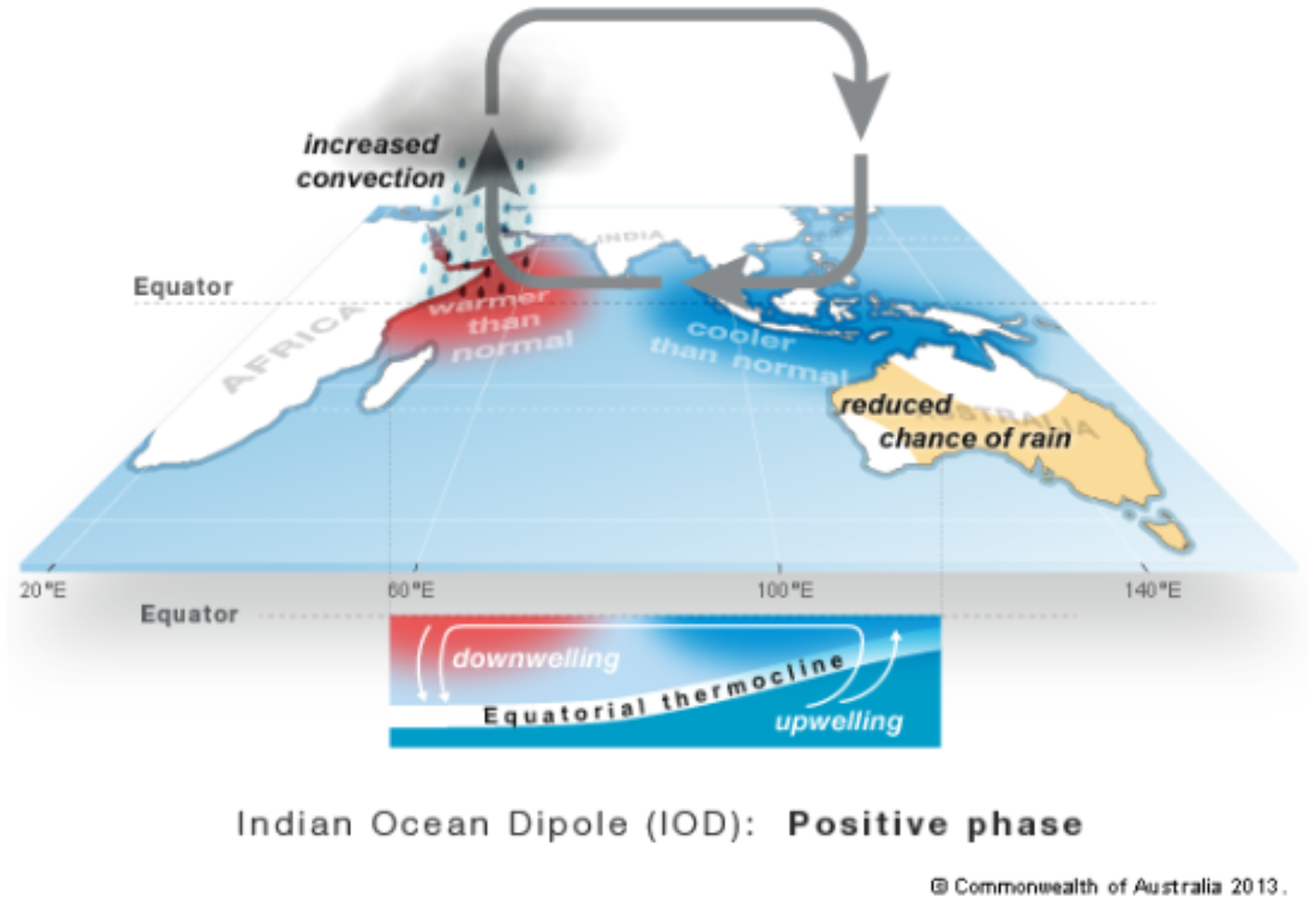

What is the IOD

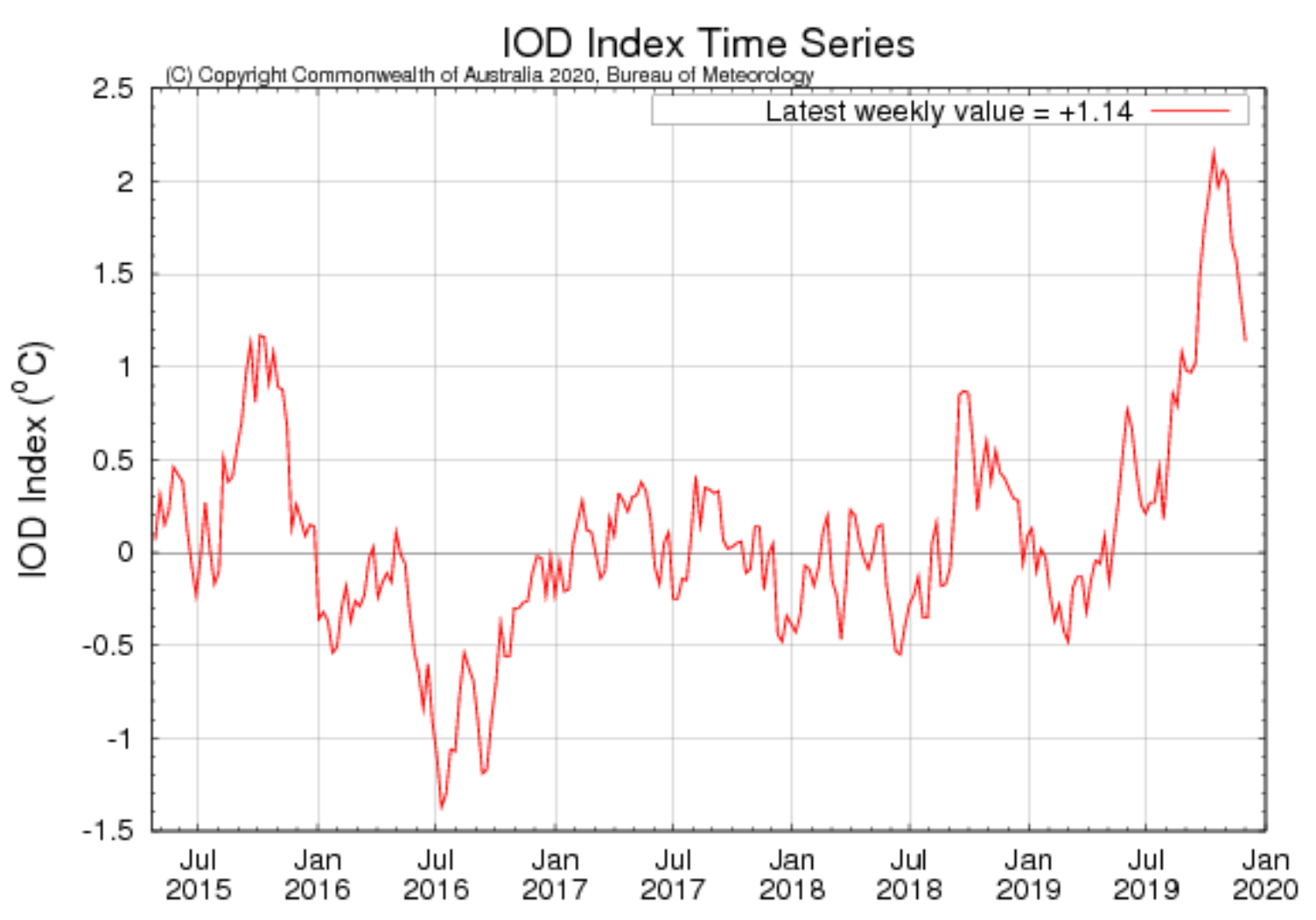

The IOD is characterized by cooler waters to the northwest of Australia, south of Indonesia, and warmer waters west towards Africa. The positive IOD contributed to low rainfall over southern and central Australia during winter months and with just as small short reprieve during last Australian summer (Dec – April) since May 2019 the IOD has been positive contributing to this overall dry pattern. In combination with reduced rainfall, positive IOD events also lead to reduced humidity across Australia. Recent months have seen notably low humidity, which enhances potential evaporation. A positive IOD is likely to remain the dominant climate driver for Australia, but, seasonally, the IOD events typically transform during the early summer as a large scale monsoon trough moves into the Southern Hemisphere which is why the IOD index below is coming off one of its strongest level in 60 years.

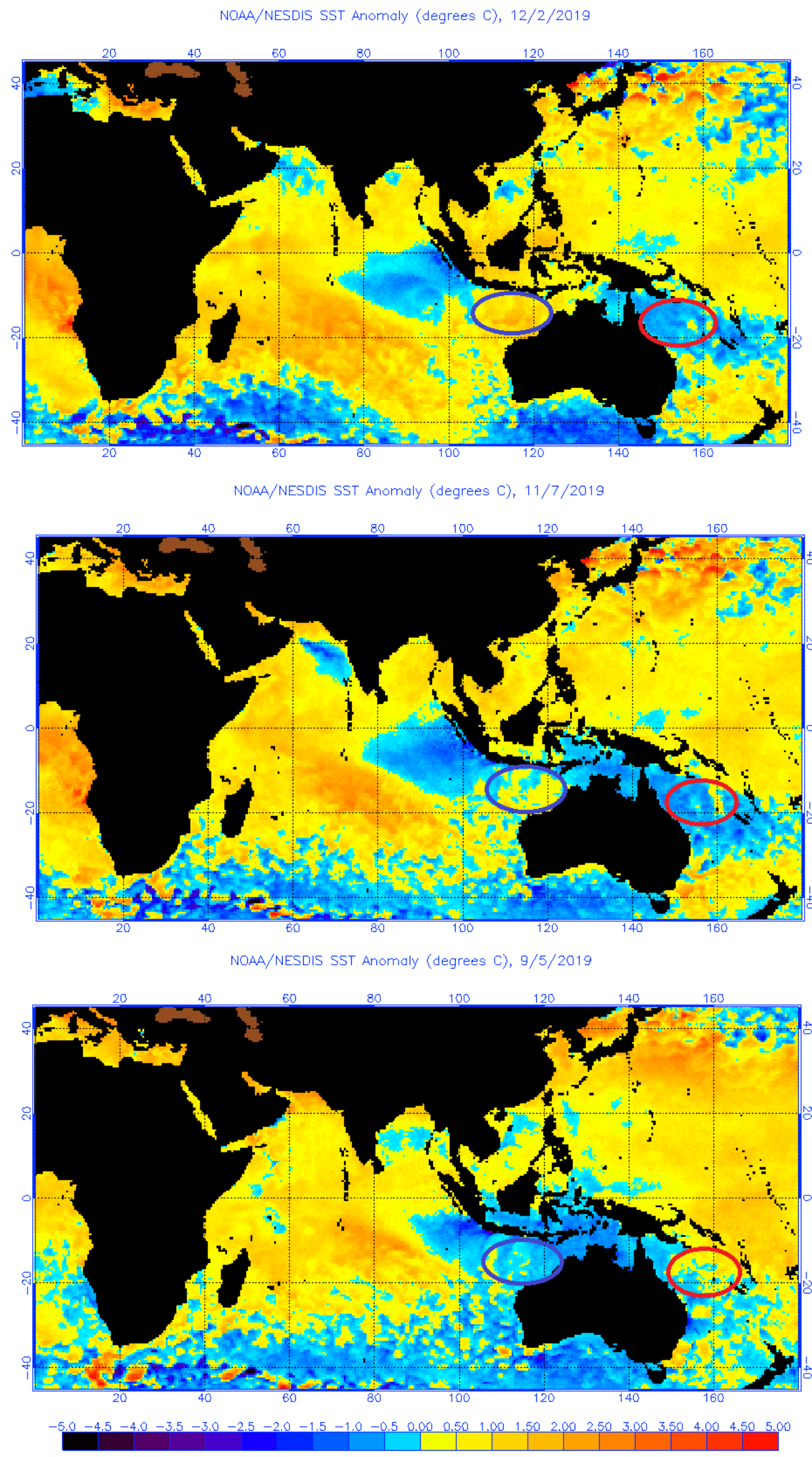

The IOD has less impact on the South Pacific cyclone season. This tends to be influenced by ENSO, which was slightly positive in a weak El Niño state about a year ago helping to explain the lack of activity for the South Pacific cyclone season, which was below average with no cyclones making landfall along the more populated east coast of Australia last year. The IOD has more influence on the cyclones that form in the northern and western regions of Australia. Since the IOD is currently positive, the overall effect should result in below-average activity for these coastal sections of Australia, which are less populated, but also contain large mining areas which could easily be impacted from cyclones that make landfall. A positive IOD should also point to higher-than-normal activity over the southwest Indian Ocean, which is where early season cyclone activity is already forming. As the season progresses, keep an eye on the SST. Over the last three months there has been warming in the waters northwest of Australia – one of the key ingredients to named storm formation. Although the current forecast is for below-normal activity, signs point to low confidence in this forecast due to the increase in water temperatures over the last few months. Overall, cyclone formation will come in waves and will rarely be spread evenly throughout the season. Quiet periods can easily be followed by bursts of activity driven by climate forcers such as the Madden Julian Oscillation, which circulates the tropics as a 30 to 60 day oscillation. Keep an eye on this climate forcer as well.

Bottom-line for Australian Summer

Australia will experience more heatwaves and bush fires during summer, but fewer cyclones could make landfall. At least one tropical cyclone has crossed the Australian coast each year since reliable records began in 1970 with four occurring in a typical year. However, with fewer-than-average numbers expected in the various cyclone regions, this should ultimately lower the landfall probability of a named storm crossing the Australian coastline. However, the now warmer-than-normal SST northwest of Australia provides lower confidence in the overall number of cyclones that could form, possibly leading to more cyclones and more landfalls in this region of Australia. With a neutral ENSO and colder-than-normal SST off the northeast coast, below-average cyclone activity is expected.

There should also be less overall severe weather events across Australia, but this does not mean that severe weather with damaging perils like hail won’t occur. Australian summer can be hectic, and although the climate forcers suggest less risk overall due to neutral ENSO and positive IOD, wild weather will happen. One should not get complacent as severe weather season can last well into April, and it only takes one thunderstorm to cause flash flooding or hail damage and insured loss. Although many of the bush fires are started by humans, some still occur naturally from lightning strikes, so this risk will last well into the summer months.