There is an old proverb used to describe the Atlantic hurricane season: “June - too soon; July - stand by; August - come they must; September - remember; October - all over.” In fact, we suggested in our May BMS Tropical Insight that the next best opportunity for tropical storms was going to be in early July. It appears that June was indeed too soon for tropical threats to the U.S. coastline. However, with the start of July, that is expected to change with development appearing likely in the northern Gulf of Mexico later this week and into the weekend.

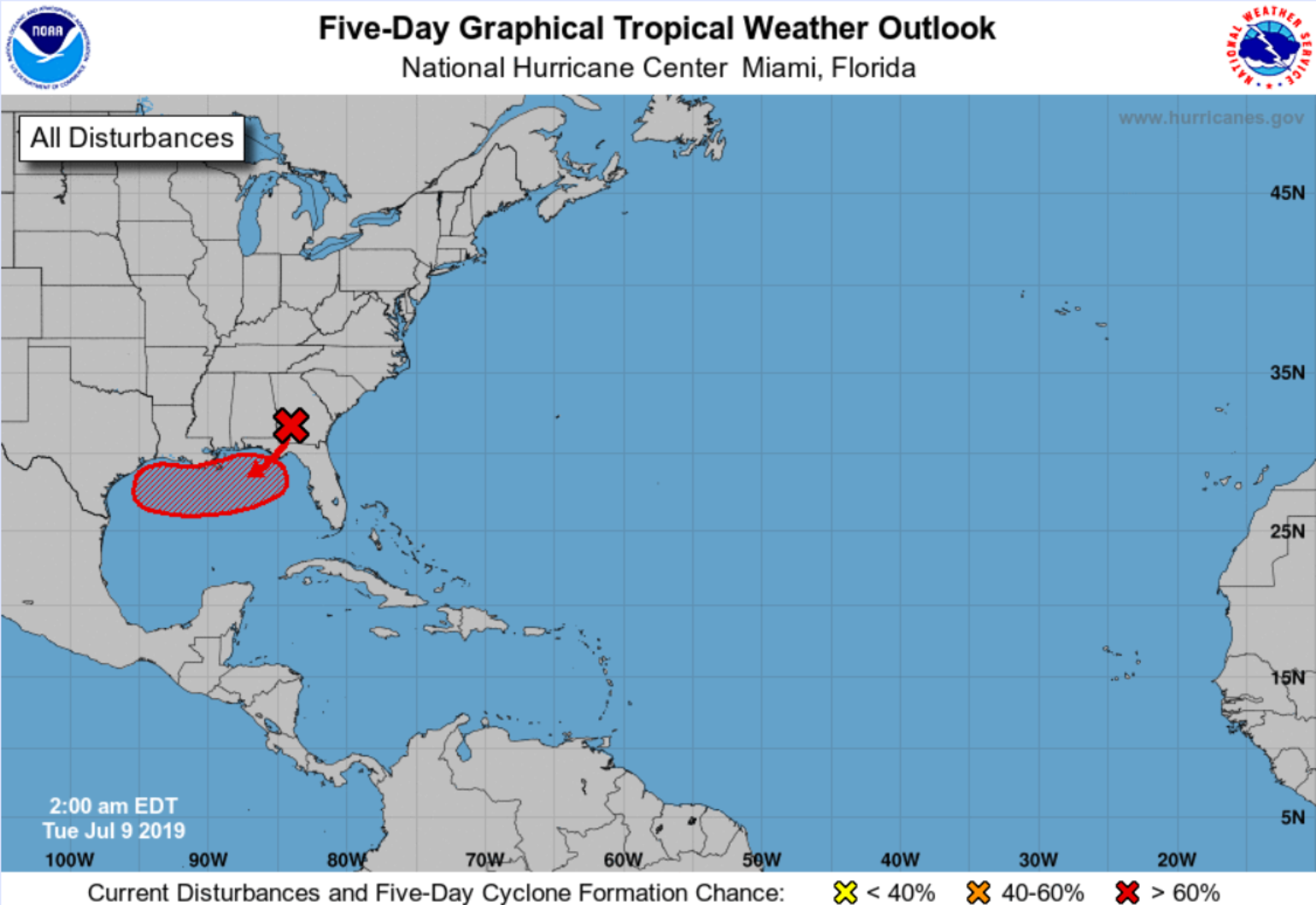

A precursor vorticity center (areas of spin) is currently heading south through Georgia and will emerge into the northeast Gulf of Mexico by Wednesday. This circulation will take advantage of warm water in the area to build thunderstorms and may slowly intensify into a tropical system.

Dry air and dust from a few major outbreaks of Saharan dust have battered most of the Atlantic basin for the last several weeks. This combined with strong wind shear has prevented tropical development across the Atlantic basin since Subtropical Storm Andrea briefly roamed the waters of the west-central Atlantic in late May.

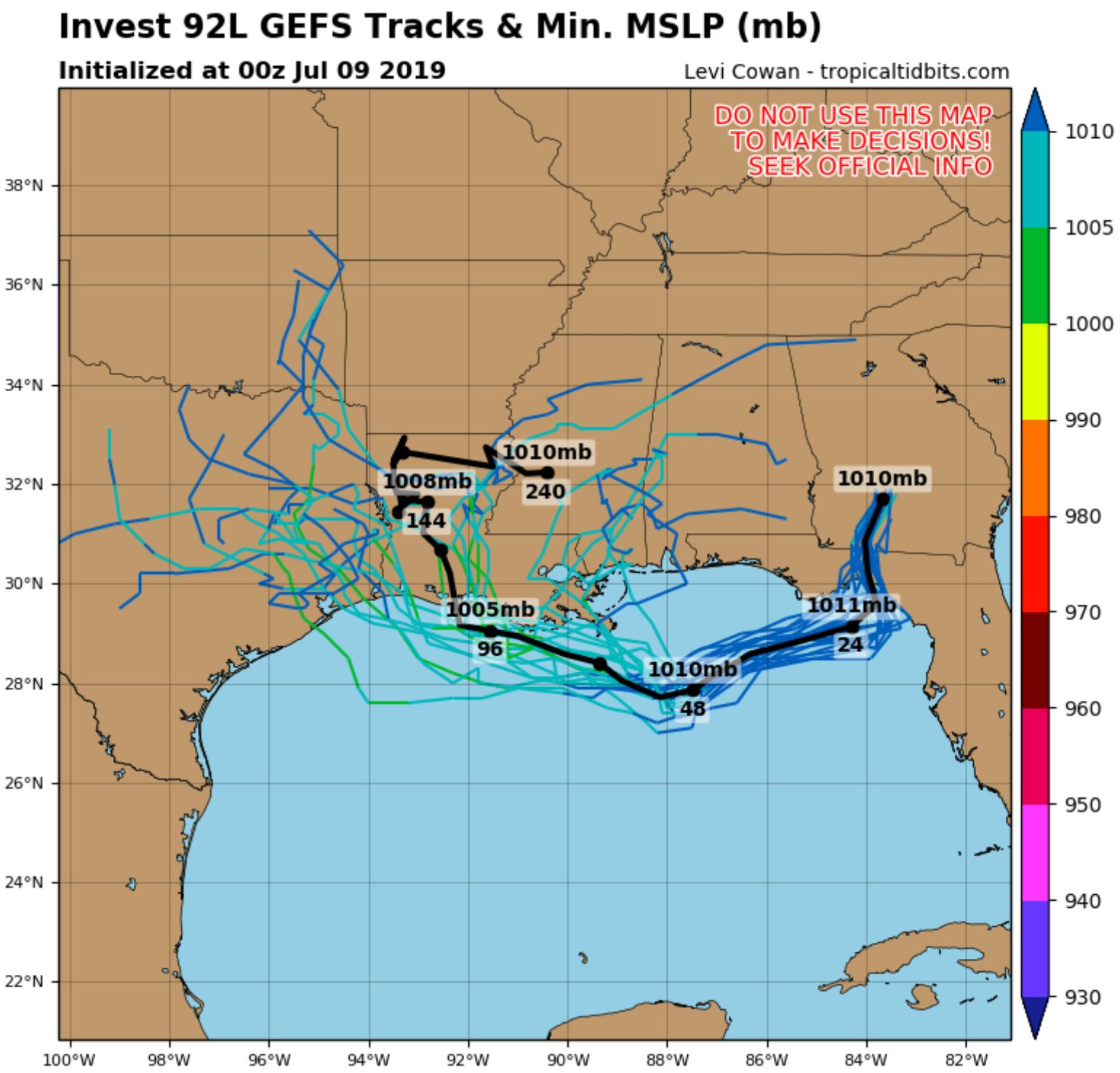

With the Madden-Julian Oscillation (MJO) currently in a positive phase that supports upward motion over Central America, the absence of strong wind shear and warmer than normal waters across the Gulf of Mexico, it should not take much to organize a tropical named storm which, if it develops later this week, will be named Barry. For the last several days, the forecasted steering winds have suggested that any named storm would drift toward the central and western portions of the Gulf of Mexico this weekend. This would give it more time over open water and could potentially create a stronger storm. With this track the risk to the insurance industry grows due to the large amount of exposure in the Houston areas, the risk to offshore assets increases due to a number of petroleum rigs and refineries along the central and western Gulf Coast. Regardless of how much development we see, the forecast models are suggesting multiple days of showers and thunderstorms that could potentially bring flooding to the southern Plains, lower Mississippi Valley and/or the southern Appalachians starting this weekend and into next week, depending on the track and timing of the storm. Some models take the tropical storm as far west as Houston which has no issue flooding from even the smallest of weather systems. Currently, some of the guidance calls for 15" of rain over the next 7 days for the area.

The last time a named tropical system made landfall in the U.S. during the month of July was Tropical Storm Emily of 2017. Emily formed in the eastern Gulf of Mexico and moved into the central Florida Peninsula on the last day of July, so it’s not unusual to see the forecast of such an event happening this week. As I mentioned in our May BMS Insight, it appears that this season’s tropical activity will be more likely to develop closer to the U.S. coastline instead of out in the Main Development Region (MDR) of the Atlantic Ocean. The bigger question is just how much activity we’ll see this season as we move toward its climatological peak at the beginning of September.

Forecasters continue to call for five to eight hurricanes to develop this season. July still does not look like a very active period for named storm development, as large scale sinking air will continue over much of the Atlantic basin, along with on and off bursts of Saharan dust that may keep activity to a minimum. While El Niño conditions may suppress the total number of tropical storms and hurricanes in the Atlantic basin this season, the data is suggesting that El Niño is weakening and may become a non-factor as we head into September. With the warmest ocean temperatures right along the U.S. coastline, the insurance industry should continue to watch for tropical waves coming off Africa which could potentially strengthen into named storms when they get closer to the U.S. coastline versus the MDR in a more typical season.

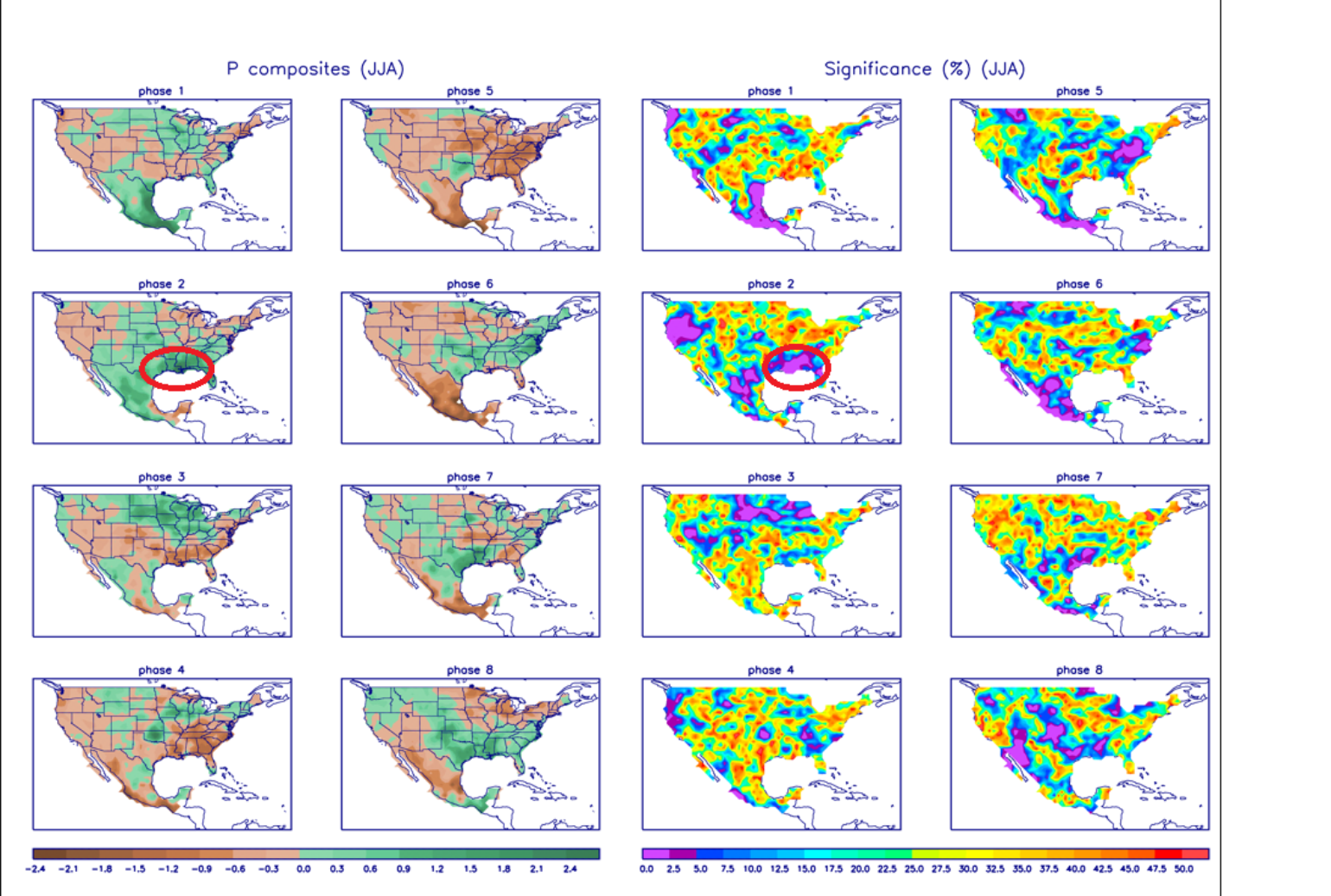

We are also now in the period where the insurance industry can begin to watch the subseasonal forecast. I have mentioned before that one of the best ways to predict this is to use the MJO, which is a pulse of upward motion that travels the tropics but also creates areas of sinking stable air in other parts of the tropics. This symbiotic pattern of wetter and drier areas moves east as a unit and typically completes a full cycle in 45 to 60 days. When the MJO (or similar phenomena) promotes upward motion over the Atlantic, hurricane development and rapid strengthening becomes much more common. According to research performed by Phil Klotzbach of Colorado State University, hurricane damage in the U.S. during convectively active phases of the MJO since the early 1900s is nearly three times greater than during suppressed Atlantic phases.

Therefore, I believe the next round of tropical storms may begin during the second week of August. Based on the current state of African waves and favorable conditions for development along the U.S. coastline, we may also be seeing an active late September and early October. Until then, keep watching the skies off the Gulf Coast and along the southeastern U.S. for the development of named storms that might not coincide with the MJO phases.